Cognitive training games were once very popular and then received bad press for lacking evidence. This included a lawsuit aimed at Lumosity in 2016 for making claims that were not backed up by science. Since then, the evidence has been mounting and we have learned a lot about what training games work and don’t work for different brain health goals and populations. The story is much more nuanced than they work or don’t work, unsurprisingly.

Here’s what we now know.

The evidence for cognitive training varies by type of training. While some structured programs show substantial benefits, particularly speed-of-processing training, which reduced dementia risk by 29-48% in the ACTIVE trial, most commercial “brain training” apps lack rigorous evidence. Physical exercise and engaged lifestyles show stronger evidence than computerized training alone.

Which Specific Types of Training Actually Work?

Speed-of-Processing Training (Strongest Evidence)

The clear winner from research. These exercises:

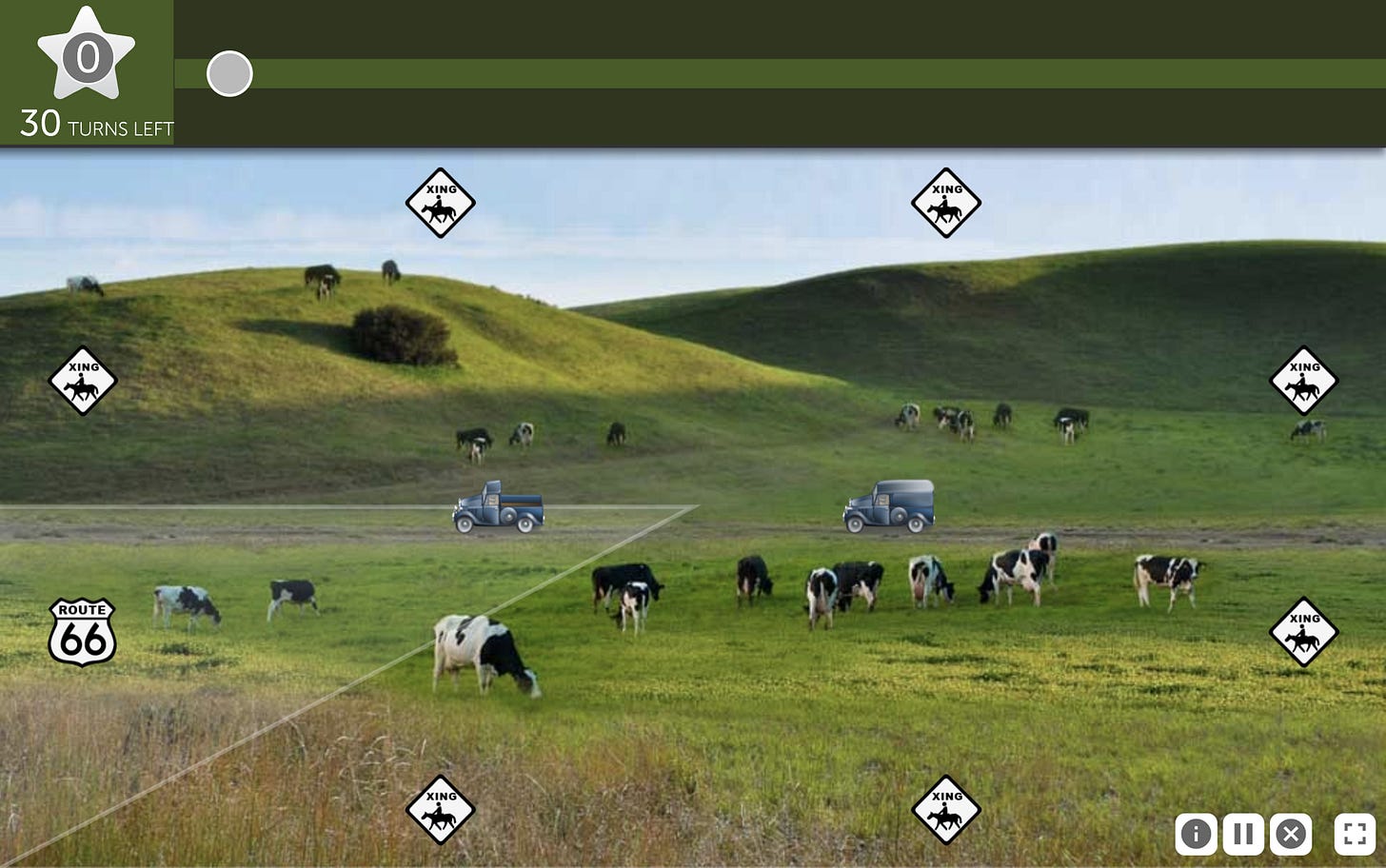

Present visual information rapidly on screen

Require quick identification of objects in peripheral vision

Progressively increase speed and difficulty

Example: The “Double Decision” task (identifying a center target while locating peripheral objects)

Results: 48% lower dementia incidence over 10 years with booster sessions, large sustained cognitive benefits (effect size 0.66). Each additional training session yielded 9% lower dementia risk.

Reasoning/Strategy Training (Moderate Evidence)

Training focused on problem-solving strategies, pattern recognition, and sequential reasoning. Showed sustained but smaller benefits (effect size 0.23 at 10 years) in ACTIVE trial. Improved self-reported daily functioning but didn’t reduce dementia risk.

Traditional Puzzles (Comparable to Apps)

Crossword puzzles: Outperformed Lumosity in head-to-head trial with MCI patients, showing less brain shrinkage and better functional outcomes. Regular solvers performed like people 8-10 years younger on cognitive tests.

Sudoku and number puzzles: Associated with sharper cognition in older adults, with frequent users showing better attention and reasoning.

Video Games

Regular video gaming shows promising associations with cognitive health, though evidence varies by game type:

3D exploration games (Super Mario-style): NIA-funded research found 3D video games improved hippocampal-based memory in older adults, with Super Mario players performing better than those playing 2D games like Angry Birds. Benefits persisted after gameplay ended.

Virtual reality games: UCSF’s Labyrinth-VR study found VR navigation games improved high-fidelity memory in older adults with 75 out of 100 cognitively average older adults performing like average college-aged players after training.

Large-scale epidemiological evidence: A UK Biobank study of 471,346 participants found computer gaming was associated with decreased dementia risk, improved cognitive function, and better brain structure. Mendelian randomization analysis suggested a possible causal relationship.

Caveats: A systematic review of serious games, which were defined as games that have the primary purpose of learning and education rather than entertainment, for dementia found improvements in memory (SMD=0.27), depression (SMD=-1.26), and global cognition (SMD=0.42), but VR technology did not significantly affect cognitive abilities when using broader prediction intervals.

Racquet Sports Games and Open-Skill Exercise (Strong Emerging Evidence)

Racquet sports (tennis, table tennis, badminton, pickleball) represent a particularly promising category because they combine aerobic exercise with rapid cognitive demands—what researchers call “open-skill exercise” (OSE).

Open-skill vs. closed-skill exercise: Open-skill exercises occur in unpredictable environments requiring constant adaptation (racquet sports, team sports), while closed-skill exercises occur in stable, self-paced environments (running, swimming, cycling). A meta-analysis of 19 studies found open-skill exercise showed superior cognitive benefits with a small effect size (g=0.30), particularly for:

Inhibition (effect size 0.25)

Cognitive flexibility (effect size 0.36)

However, no significant difference was found for processing speed between exercise types in intervention studies, despite cross-sectional evidence that racquet sport players have faster reaction times.

Tennis players show faster processing: A study of long-term tennis players (10+ years) found significantly faster simple reaction time (323ms vs 391ms) and choice reaction time (518ms vs 579ms) compared to walkers, swimmers, and runners—even when matched for overall physical activity levels. This suggests the cognitive demands of tracking a fast-moving ball and making split-second decisions may train processing speed over time.

Table tennis may be particularly beneficial: Reviews on table tennis for brain health suggest it may be among the best sports for dementia prevention due to:

Low-to-moderate intensity accessible to older adults

High cognitive engagement (tracking spin, anticipating shots)

Social interaction component

Already used clinically as “table tennis therapy” for cognitive impairment

Longevity benefits: A study of ~80,000 people found racquet sports linked to 47% lower risk of all-cause mortality. Tennis specifically was associated with 9.7 additional years of life expectancy compared to sedentary individuals—more than swimming (3.4 years), cycling (3.7 years), or jogging (3.2 years).

Biological mechanisms: Open-skill exercise induces higher BDNF release than closed-skill exercise. BDNF (brain-derived neurotrophic factor) promotes neuronal survival, brain plasticity, and may help clear amyloid-β plaques associated with Alzheimer’s disease.

The caveat on processing speed: While racquet sport players consistently show faster reaction times in cross-sectional studies, meta-analyses of intervention studies don’t show open-skill exercise improves processing speed more than closed-skill exercise. This may reflect selection bias (people with faster processing are drawn to racquet sports), or benefits may require very long-term participation not captured in short intervention trials.

Memory Training (Weakest Evidence)

Surprisingly, traditional memory training (remembering word lists, mnemonic strategies) showed the least benefit in the ACTIVE trial with no long-term cognitive improvements or dementia risk reduction. This matters because many brain training apps focus primarily on memory games.

For healthy older adults, all these interventions show limited “far transfer”, meaning getting better at crosswords makes you better at crosswords, but doesn’t necessarily improve everyday abilities like managing finances or remembering appointments.

Evidence Overview: What the Research Actually Shows

Meta-Analyses Reveal Modest, Domain-Specific Benefits

Multiple systematic reviews show small to moderate effects highly specific to trained domains. For healthy older adults, overall effect size is g=0.22—statistically significant but small. Processing speed shows moderate benefits (g=0.31), while executive function shows no improvement (g=0.09).

For mild cognitive impairment (MCI), evidence is more encouraging: supervised training produced moderate effects on verbal memory (SMD=0.72) and working memory (SMD=0.33).

Training frequency matters: 2-3 sessions weekly produced optimal results, while more than 3 sessions showed no benefit, possibly due to cognitive fatigue. Benefits plateaued after 19-36 total hours with diminishing returns beyond that.

The ACTIVE Trial: Gold Standard Evidence

The Advanced Cognitive Training for Independent and Vital Elderly trial followed 2,832 older adults for 10 years, testing memory, reasoning, and speed-of-processing training. Speed training produced large, durable benefits while memory training failed to show long-term benefits.

Multidomain Approaches Show Promise

The Finnish FINGER trial combined nutrition, exercise, cognitive training, vascular monitoring, and social activity in at-risk older adults, producing benefits across multiple domains including 25% improvement in processing speed. However, other multidomain trials (MAPT, preDIVA) found no significant effects, likely reflecting differences in population selection and intervention intensity.

Commercial Apps vs. Traditional Activities

Commercial Programs

Lumosity faced a $2 million FTC fine in 2016 for claims lacking scientific backing. One major trial found Lumosity showed improvements only on tasks highly similar to training exercises (minimal far transfer).

BrainHQ has the strongest commercial evidence base, with its speed exercises used in ACTIVE and multiple independent RCTs showing benefits in specific populations. However, evidence is exercise-specific, and the ACTIVE protocol was supervised, unlike typical home use.

Who Benefits Most?

Mild cognitive impairment: Strongest effects (g=0.35), considerably larger than healthy older adults (g=0.22). Meta-analyses find benefits across multiple domains, though effects fade after training stops.

Post-stroke: Moderate effects on general cognitive function (SMD=0.46). Short-term intensive training (≤6 weeks) showed large effects (SMD=0.68) while longer training showed no benefit, suggesting intensive bursts beat prolonged low-frequency training.

Cognitive Training for Traumatic Brain Injury (TBI)

TBI represents one of the more promising applications for cognitive training, with stronger evidence than for healthy older adults.

The BRAVE Trial: Landmark Evidence for Mild TBI

The Department of Defense-funded BRAVE study provides the strongest evidence for computerized cognitive training in TBI. This randomized controlled trial enrolled 83 veterans with persistent cognitive deficits averaging 7+ years after mild TBI (concussions and blast injuries).

Key findings:

BrainHQ group showed 3.9 times greater cognitive improvement than computer games control group immediately after training

Benefits grew to 4.9 times larger at 12-week follow-up

77% of BrainHQ users improved in cognitive function vs. only 38% of control group

Participants improved by an average of 24 percentile ranks (from 50th to 74th percentile)

Training was delivered remotely via telehealth with weekly phone coaching

This is the first computerized cognitive training shown effective in a gold-standard trial for mTBI

Limitations: Functional and self-report measures did not show significant between-group differences, though both groups improved on many measures.

Meta-Analytic Evidence for TBI Rehabilitation

Multiple meta-analyses support cognitive rehabilitation for TBI:

Digital cognitive interventions: A 2025 meta-analysis of 16 RCTs found digital (computer- and VR-based) cognitive training significantly improved global cognitive function in TBI patients (SMD=0.64, 95% CI: 0.44-0.85, p<0.001). VR-based training showed even larger effects (SMD=0.92) compared to conventional face-to-face rehabilitation.

Post-acute TBI: A systematic review and meta-analysis found cognitive training produced small but significant effects on overall cognition (g=0.22, 95% CI: 0.05-0.38) with low heterogeneity and no publication bias.

Military/Veteran populations: A meta-analysis of cognitive rehabilitation in Veterans/Service Members with TBI found evidence of cognitive improvement, with clinician-administered interventions focusing on teaching strategies yielding the greatest benefits.

Pragmatic language: Cognitive rehabilitation targeting communication skills showed large positive effects (Cohen’s d=0.89) on improving pragmatic language abilities in TBI patients.

What Works Best for TBI

Evidence suggests effective TBI cognitive rehabilitation should include:

Speed-of-processing and attention training (strongest evidence from BRAVE trial)

Compensatory strategy training administered by clinicians

Attention Process Training for attention deficits

Errorless learning for memory deficits

Problem-solving and metacognitive training for executive dysfunction

Remote/telehealth delivery can be as effective as in-person for appropriate patients

Important context: Current best practices still focus on in-person, customized cognitive rehabilitation, which is costly and time-consuming. The BRAVE trial suggests computerized training may provide a scalable alternative, particularly for those with limited access to specialized care.

Durability: Benefits Fade Without Continued Practice

Long-term follow-up reveals cognitive training benefits fade without ongoing practice. ACTIVE participants receiving booster sessions maintained larger benefits, with each booster session conferring an additional 10% dementia risk reduction. Cognitive training is not a “one-time inoculation” but requires ongoing engagement like physical exercise.

Optimal approach: moderate-intensity training (2-3 sessions weekly, for 16 weeks) followed by periodic boosters, rather than continuous training or brief one-time interventions.

Conclusion

Speed-of-processing training has the strongest evidence (29-48% dementia risk reduction over 10 years), but requires periodic booster training. For MCI, supervised cognitive training produces moderate benefits (effect size 0.35-0.55). For traumatic brain injury, evidence is particularly encouraging, the BRAVE trial showed cognitive improvements 3.9-4.9 times greater than controls, with 77% of participants improving.

Traditional puzzles, video games (especially 3D/strategy games), and racquet sports are equally as effective as brain training apps. Racquet sports may be particularly valuable as they combine aerobic exercise with cognitive demands, and tennis players show 9.7 additional years of life expectancy.

For cognitive health, prioritize:

Physical exercise (strongest evidence), especially open-skill activities like racquet sports that combine aerobic demands with cognitive challenges

Healthy lifestyle (see NeuroAge’s Nine Pillars of Healthy Brain Aging)

Cognitive training as a supplement, not substitute, for comprehensive brain health

I LIKE how you tease out the differences between speed-of-processing training, traditional puzzles, open-skill exercise, and the limitations of most commercial apps.

What stood out most to me was the emphasis on domain specificity and the reminder that cognitive training isn’t a one-time intervention but something that requires ongoing engagement, much like physical exercise. That aligns completely with what I see in clinical practice with patients recovering from medical illness, TBI, or long-term stress exposure — improvements happen, but they’re sustained only when the habits do.

The emerging evidence on open-skill activities and the interaction between aerobic exercise, cognitive load, and BDNF is especially compelling. It’s refreshing to see racquet sports, VR navigation tasks, and structured speed training all discussed in the same framework rather than in isolation.