Exercise for Cognitive Sharpness and Dementia Prevention

What type and amount of exercise is the most beneficial

I’m often asked which of the 9 pillars of healthy brain aging has the largest impact on staying cognitively sharp. Exercise and sleep are #1 and #2.

Here I take a deep dive into the optimal exercise routine for brain health and how it can be personalized to your MRI findings, genetics, and biomarkers.

Exercise Guidelines for the Brain at a Glance

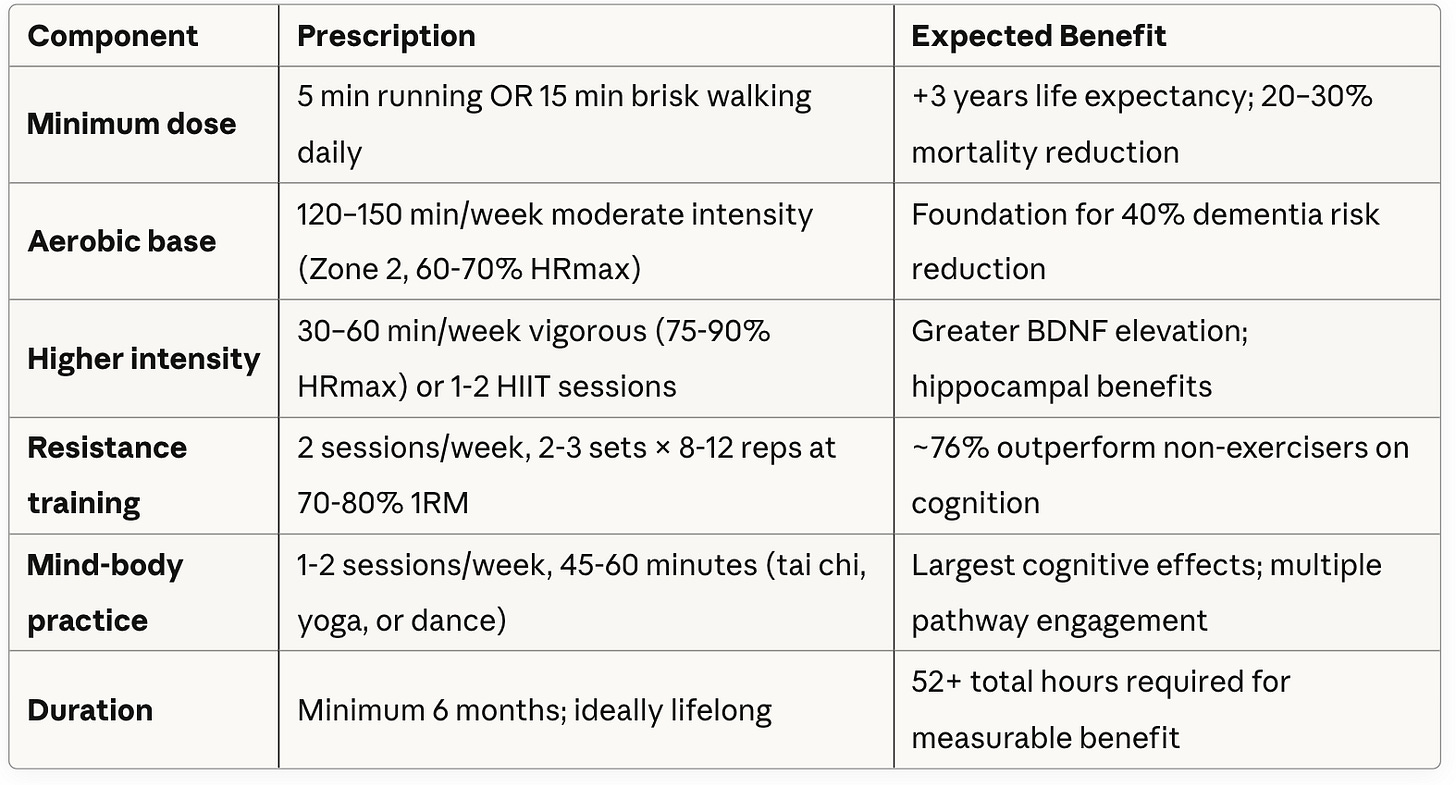

Combined aerobic and resistance training provides the strongest protection against cognitive decline, with 40% dementia risk reduction linked to high cardiorespiratory fitness. The benefits begin at remarkably low thresholds, as little as 5 minutes of running or 15 minutes of brisk walking daily, and scale upward until plateauing around 1-2.5 hrs/day. Mind-body practices like tai chi show unexpectedly large effects, warranting their inclusion in any cognitive health program.

The Minimum Effective Dose: How Little Exercise Still Helps?

The dose-response curve is not linear: the greatest relative benefit comes from moving from nothing to something. Whatever you can do is helpful, the key is just to start.

For Mortality

A landmark 2014 study of 55,000 adults followed for 15 years found that just 5–10 minutes per day of slow jogging was associated with:

30% reduction in all-cause mortality

45% reduction in cardiovascular mortality

+3 years added life expectancy

Similarly, 15 minutes of brisk walking daily reduced total mortality by 20% in a study of nearly 80,000 predominantly low-income adults, while more than 3 hours of slow walking daily reduced mortality by only 4%. Pace matters more than duration at lower volumes.

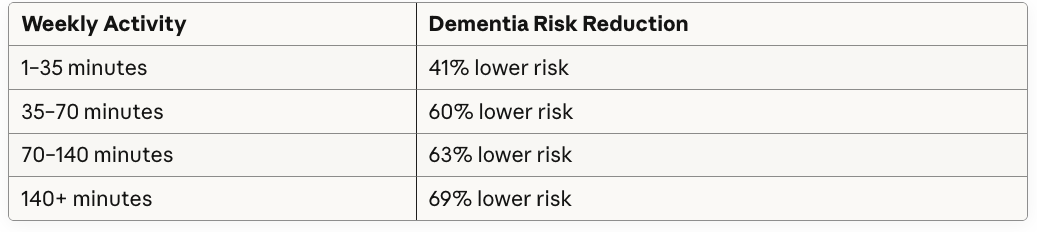

For Dementia Prevention

A Johns Hopkins analysis of UK Biobank data found striking dose-response relationships even at very low activity levels:

Even frail older adults saw comparable benefits, which suggests that physical limitations should not preclude exercise prescription.

For individuals with elevated brain amyloid (preclinical Alzheimer’s), Nature Medicine research found that benefits on tau accumulation and cognitive decline plateau at 5,000–7,500 steps per day (~2-3 miles), which is a surprisingly accessible threshold.

Aerobic Exercise

Aerobic exercise remains the most extensively studied modality for cognitive outcomes. A meta-analysis of 29 RCTs (n=2,049) found consistent improvements across cognitive domains, with exercisers showing better performance than approximately 55–60% of sedentary controls on attention, processing speed, and memory measures.

A 2025 British Journal of Sports Medicine study following 61,214 participants over 12 years found high cardiorespiratory fitness reduced dementia risk by 40% compared to low fitness, delaying onset by nearly 1.5 years. Remarkably, a Swedish 44-year follow-up study found women with high midlife cardiovascular fitness had 88% lower dementia risk and experienced a 9.5-year delay in disease onset. Each 3.5 mL/kg/min increase in VO2max translates to approximately 20% decreased dementia risk.

High-intensity interval training (HIIT) shows particular promise for executive function. A 2024 meta-analysis of 20 RCTs found HIIT produced moderate effects on executive function, with adults over 60 showing the strongest response. Approximately 70% of HIIT participants outperformed average controls on information processing tasks.

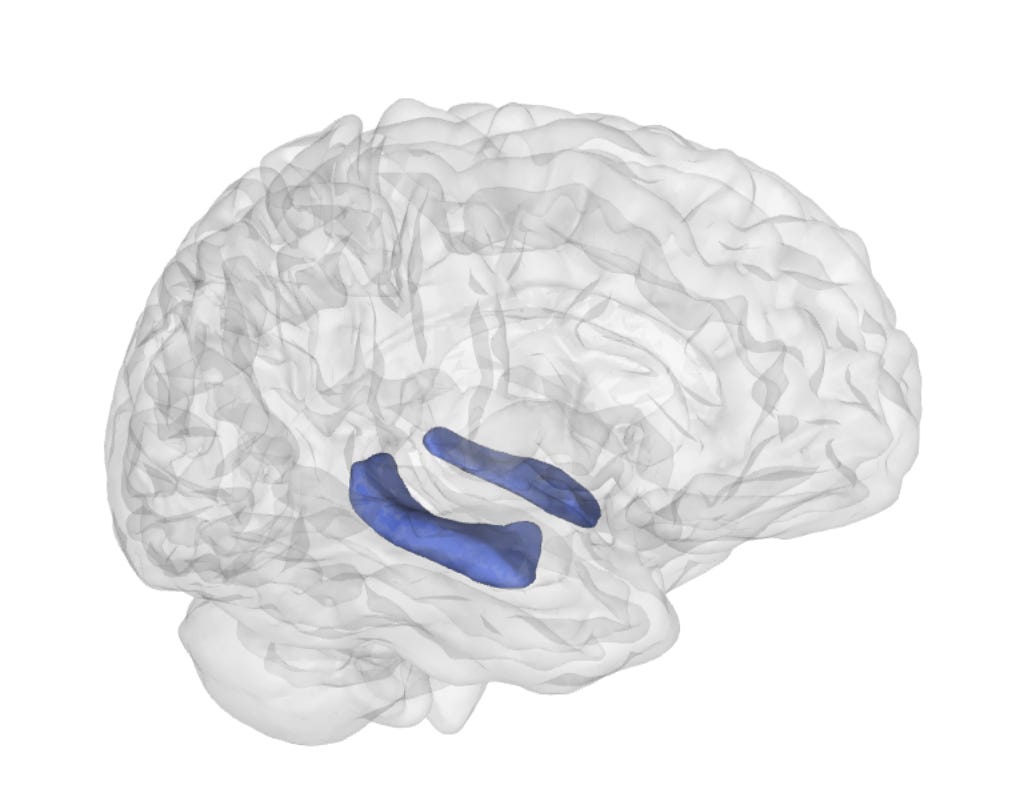

Notably, a University of Queensland 6-month intervention found HIIT-related learning improvements persisted up to 5 years post-intervention, with preserved right hippocampal volume visible on MRI.

The hippocampus is the area of the brain that stores short-term memories and decreases in size in Alzheimer’s Disease and Mild Cognitive Impairment (MCI). It decreases due to loss of neurons and loss of the connections between neurons. To have optimal memory and prevent Alzheimer’s, the goal is to keep the hippocampus the same size as you age or even increase its size. HIIT has the most evidence of any exercise for being able to do that.

Resistance Training

Resistance training provides cognitive benefits through mechanisms partially independent of aerobic exercise. The Landrigan “Lifting Cognition” meta-analysis (24 studies, n=1,642) found that ~76% of strength trainers showed better cognitive performance than the average non-exerciser on composite measures, and ~90% showed improvement on cognitive screening tests compared to controls.

Interestingly, resistance training particularly benefits executive function (planning, problem-solving, and inhibition) and attention rather than memory. A meta-analysis focusing on MCI patients found resistance training improved executive function significantly (~69% outperformed controls) but not working memory (very short-term memory like remembering a phone number). Twice-weekly sessions outperformed three times weekly, and sessions exceeding 60 minutes showed superior effects.

The unique mechanisms of resistance training include:

IGF-1 pathway activation promoting neurogenesis

Prefrontal cortex plasticity enhancing attention and visuospatial processing

65% increase in plasma BDNF following 10-week programs

Reduced cortical white matter atrophy with year-long programs

Combined training appears superior to either modality alone. A 2025 meta-analysis of 35 RCTs (n=5,734) found combined aerobic and resistance training improved global cognition, with approximately 63% of combined-training participants outperforming average controls. McKnight Brain Research Foundation data showed adults aged 85-99 who engaged in both modalities had superior cognitive performance compared to those doing cardio alone.

Mind-Body Practices: Surprisingly Large Cognitive Effects

Mind-body exercises demonstrate the largest effects for cognitive outcomes in head to head comparisons, a finding that challenges conventional assumptions about exercise and brain health. An umbrella review of 20 meta-analyses found that approximately 68% of mind-body exercise participants showed better cognition than the average non-exerciser, compared to only 57% for aerobic exercise and 60% for resistance exercise participants.

Tai chi shows particularly robust effects. A systematic review of 20 studies (n=2,553) found approximately 82% of tai chi practitioners outperformed average non-exercisers on executive function in healthy adults, and 69% outperformed those doing other exercise types. Most remarkably, one RCT showed only 4.3% of the tai chi group progressed to dementia compared to 16.6% in the Western exercise control group.

Dance interventions combine physical, cognitive, and social elements with strong outcomes. A 2025 umbrella review synthesizing 10 systematic reviews found approximately 73% of dancers showed improved MoCA (Alzheimer’s cognitive test) scores compared to controls. Network meta-analysis identified ballroom dancing as most effective, with approximately 81% outperforming controls on cognitive function measures.

Yoga produces moderate, consistent effects across cognitive domains. A meta-analysis of 12 studies (n=912) found approximately 65% of yoga practitioners outperformed controls on memory, executive function, and attention.

The superior effects of mind-body practices likely stem from their combination of moderate aerobic activity, motor learning, attentional training, meditation/relaxation, and social engagement, effectively engaging multiple neuroprotective pathways simultaneously.

Heart Rate Zones and Intensity

Moderate intensity (60-85% HRmax) shows the most consistent evidence across meta-analyses. However, different intensities may engage different mechanisms:

Zone 2 training (60-70% HRmax) supports fat oxidation, mitochondrial function, and sustained cerebral blood flow.

Higher intensity (≥85% HRmax) produces greater lactate elevation, which crosses the blood-brain barrier and directly stimulates BDNF production. HIIT generates larger acute BDNF spikes and may provide superior hippocampal benefits based on long-term follow-up data.

Practical heart rate guidance:

Base building: Zone 2 (60-70% HRmax) for majority of aerobic volume

Cognitive enhancement: Include 1-2 sessions weekly at vigorous intensity (75-90% HRmax)

HIIT: Intervals at 85-95% peak heart rate with recovery periods for increasing hippocampal size and function

The Upper Limit: Is There Such a Thing as Too Much?

For Mortality and General Health

The threshold for harm is far higher than most people will ever reach. A pooled analysis of 661,137 individuals found:

Maximum mortality benefit occurred at 3–5× current guidelines (~1-2 hrs/day)

Individuals exercising at 10× the recommended minimum (~5hrs/day) still showed 31% lower mortality than inactive people

No evidence of increased mortality risk even at 10× guidelines

A 30-year Harvard study of 100,000+ adults confirmed: those performing 2–4× recommended activity (42-84 mins/day on average) had 26–31% lower all-cause mortality, with no harmful cardiovascular effects at even higher levels.

The “Extreme Exercise Hypothesis”

However, the “Extreme Exercise Hypothesis” proposes potential harm at very high chronic doses. The evidence is most convincing for atrial fibrillation (AF):

A U-shaped dose-response relationship has been identified between cumulative lifetime endurance training hours and AF risk:

<2,000 lifetime hours of high-intensity exercise: 62% lower AF risk

>2,000 lifetime hours: Nearly 4× higher AF risk

To put 2,000 hours in perspective: that’s roughly 10 years of training 4 hours per week.

Elite endurance athletes show higher coronary artery calcium scores but paradoxically have lower cardiovascular mortality and 3–6 year longer life expectancy than the general population. The elevated calcium may represent plaque stabilization rather than increased risk.

This AF risk has not been consistently demonstrated in female athletes, who may be protected by hormonal or other factors.

Overtraining Syndrome and Cognitive Effects

Overtraining syndrome (OTS) represents a maladapted response to excessive exercise without adequate recovery, affecting 5–60% of professional athletes at some point. Symptoms include:

Cognitive problems: difficulty concentrating, slower reaction times, brain fog

Mood disruption: depression, anxiety, irritability

Sleep disturbance

Persistent fatigue and decreased performance

A systematic review found that reaction time worsens with overtraining, and cognitive function is impaired in athletes experiencing non-functional overreaching.

Recovery is the critical variable. OTS is about insufficient recovery relative to training load rather than an absolute upper limit on exercise.

For beginners and youth, 2 days off/week from training is recommended. For elite athletes, at least 1 day off/week is ideal to promote recovery and avoid OTS.

The Neurobiology: Why Exercise Protects the Brain

Exercise engages multiple, complementary neuroprotective mechanisms.

BDNF remains the best-characterized mediator. A meta-analysis of 29 studies found acute exercise produces moderate BDNF elevation, while regular training enhances this effect further. Both aerobic and resistance exercise increase BDNF. BDNF promotes neurogenesis and synaptic plasticity.

Hippocampal volume changes provide the most direct structural evidence. The landmark Erickson 2011 PNAS study randomized 120 older adults to aerobic exercise versus stretching for one year. The aerobic group showed 2% hippocampal volume increase while controls declined 1.4%, effectively reversing 1–2 years of age-related atrophy. Changes correlated with serum BDNF and improved spatial memory. Women with MCI showed even larger effects: 5.6% left hippocampal volume increase after 6 months of aerobic exercise.

Cerebrovascular improvements include enhanced cerebral blood flow, angiogenesis via VEGF upregulation, and improved pulsatility indices. A 12-week exercise intervention in MCI patients reversed abnormal perfusion patterns and improved working memory.

Lactate functions as a signaling molecule, not merely metabolic waste. El Hayek et al. (2019) demonstrated that lactate crosses the blood-brain barrier, activates SIRT1 in hippocampal neurons, and directly induces BDNF expression in mice.

Anti-inflammatory effects target neuroinflammation central to Alzheimer’s pathology. Exercise shifts microglial phenotype from pro-inflammatory M1 to anti-inflammatory M2, suppresses the NLRP3 inflammasome, and decreases IL-6, TNF-α, and CRP.

MCI Populations: Adapted but Intensive Approaches

For individuals with mild cognitive impairment, exercise shows moderate benefit for cognitive function. Network meta-analysis of 71 RCTs (n=5,606) found multicomponent exercise most effective for MCI—approximately 84% of multicomponent exercise participants showed better global cognition than average controls, and 76% showed improved executive function.

The largest observational study on conversion risk—a Korean cohort of 247,149 MCI individuals followed for 6 years—found:

Maintaining physical activity reduced dementia conversion by 18%

Initiating activity after MCI diagnosis still reduced risk by 11%

Threshold: moderate-intensity exercise ≥5 days/week or vigorous-intensity ≥3 days/week

Mind-body exercise shows particular promise for MCI. Tai chi reduced progression to dementia to 2.2% versus 10.8% in stretching controls in one year-long RCT.

The Ideal Exercise Prescription in General

In total, the ideal brain workout schedule is about 1 hr and 20 mins per day, 6 days a week, evenly split between moderate intensity aerobics, HIIT, resistance training, and mind-body (dance, yoga, or tai chi). This should last for at least 6 months to see cognitive benefits, ideally for life.

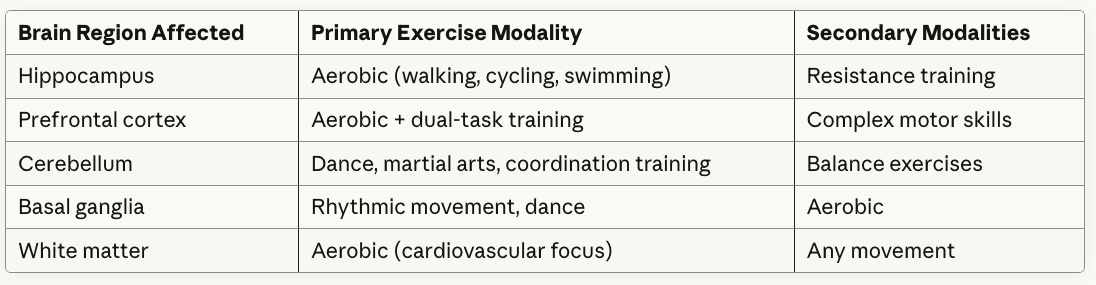

Personalized Exercise Routines Based on MRI Findings, Genetics, and Biomarkers

Personalized exercise routines based on your brain region volumes, genetics, and biomarkers are the wave of the future. At NeuroAge we customize your exercise recommendations depending on which brain regions we see could use the most volume boost. We recommend postural training and balance-rich exercises like soccer for people who have lower than ideal cerebellum volume, for instance. The cerebellum is the brain’s balance center and randomized control trials have shown that the aforementioned types of exercise can increase its volume.

Matching Exercise to Brain Region Atrophy:

Blood levels of inflammatory biomarkers such as IL6 and CRP can inform the types of exercise that are working for you and how much recovery you ideally need. Certain genetic markers and your cognitive performance also inform which exercises might work best to improve your brain health.

Key implications for APOE4 carriers:

They may show blunted BDNF response to exercise (particularly APOE4 homozygotes)

However, they may benefit more in other domains (executive function, telomere length)

Higher doses of exercise may be necessary to achieve equivalent benefit

The protective effect of exercise on hippocampal volume appears preserved

Consider multimodal approaches (exercise + other interventions) to compensate for blunted BDNF signaling

Conclusion

Physical exercise stands as one of the most powerful modifiable factors for cognitive health and dementia prevention—with 40% risk reduction achievable through high cardiorespiratory fitness and benefits beginning at remarkably low thresholds.

The most important message is that something is dramatically better than nothing. Five minutes of running or 15 minutes of brisk walking daily adds approximately 3 years to life expectancy and initiates the cascade of neuroprotective effects. Benefits then scale with dose, plateauing around 1-2 hrs/day without evidence of harm up to 5hrs/day for most outcomes. The exceptions are an increase in atrial fibrillation in male elite exercisers and an increase in osteoarthritis in contact sport players with a history of injuries.

The optimal approach combines modalities: aerobic training builds the cardiovascular foundation and drives neurogenesis, resistance training enhances executive function through distinct pathways, and mind-body practices deliver surprisingly large effects by engaging physical, cognitive, and meditative systems simultaneously.

For individuals already experiencing cognitive decline, multicomponent exercise programs or mind-body practices like tai chi represent evidence-backed interventions that may slow progression to dementia. The window for benefit remains open even after MCI diagnosis.

Exercise can be customized to your specific brain MRI findings, genetics, and biomarkers, which creates the optimal tailored approach for your brain.

Dr. Glorioso, this breakdown is a tour de force. The distinction between "Zone 2" for vascular maintenance and "HIIT" for structural hippocampal expansion is a critical nuance that most generic advice misses. You are effectively prescribing specific architectural tools for specific renovation projects.

The data on Tai Chi outperforming traditional Western exercise for dementia prevention (4.3% vs 16.6%) is staggering. It suggests that complexity of movement - the cognitive load of motor learning - is just as vital as the metabolic load. We aren't just building an engine; we are upgrading the software. Brilliant synthesis.

Dr Tom Kane

This is such a data-rich breakdown of something patients are constantly told in vague terms: “exercise is good for your brain,” without any real guidance on how or how much. I really appreciate how you translate that into minimum effective doses, specific modalities, and even how different types of exercise map onto different brain regions and mechanisms.

The nuance around “something is dramatically better than nothing” is huge clinically. So many people shut down when they think they need the “perfect” routine to get any benefit. Hearing that 5–10 minutes of movement or a few thousand steps can actually move the needle on cognition and dementia risk is often what gets people started.

I also love the emphasis on mind–body practices and multicomponent exercise. The idea that tai chi, dance, or racquet sports may outperform what we traditionally think of as “exercise” for the brain really resonates with what I see anecdotally: people do best when movement is cognitively engaging and emotionally meaningful, not just another task on a to-do list.