Discover more from Dr. Christin Glorioso, MD PhD

How old are you really?

The promise and caveats of "aging clock" tests to determine biological age.

“How old do you think I am?” We are all familiar with this guessing game. The visual assessment of someone’s age is one form of an aging clock. And it turns out that how fast we are aging matters to health outcomes and lifespan.

Scientists are quantifying your biological age and testing what you can do to age more slowly or even reverse your biological age. Levels of RNA, modifications to proteins, and epigenetics change precisely within your cells with age. Where you are in terms of those changes compared to the average person your age can reveal your biological age. This is important for determining which lifestyle interventions or drugs might be able to slow down or reverse aging without having to wait for people to kick the bucket to know what worked. A one-man experiment run by wealthy tech entrepreneur, Bryan Johnson, has recently gotten a lot of press. He is using aging clocks to quantify his health and try and reduce his biological age. He claims that he has reduced his biological age by 5.1 years and that this is a world record. It’s not in fact a world record, as pointed out by Nikolina Lauc, CEO of GlycanAge, on Twitter- many of their own employees have reduced their bio age by more than this.

You can purchase an aging clock blood test from various companies for around $400. These costs may be prohibitive to some, but will come down in time with improving technology in the same way that genome sequencing has become more affordable. I believe that aging clock tests are going to be as common in households as 23andMe in the next 10 years. They will be used by people interested in tracking fitness and by doctor’s offices alike. There are, however, still some open questions about how accurate and precise these clocks are and what they mean for health.

To date there have been over a dozen aging clocks that examine blood samples using different measurements. Some use epigenetics, some proteomics, some use RNA levels, and some use metrics more commonly measured in doctor’s offices like cholesterol and blood pressure. The first question about clock reliability is do you get the same measurement in the same person if you test them again within a short period of time? These clocks should be stable if they are reflecting a person’s true biological age. If, for example, you measured a person’s biological age in the morning, at noon, and at night on the same day, you should get the very similar results to a very high degree. I haven’t yet seen published data on this but recent interviews and talks by experts, including Prof. Morgan Levine (Yale/Altos Labs) and Prof. Eric Verdin (Buck Institute for Research on Aging) suggest that there may still be some problems with clock precision. I would like to either run this analysis myself or see published data to verify the extent of this potential problem. It does make sense that stability would be an issue given that these are blood tests and cell numbers go up and down in the blood with hormone levels and inflammation, both of which can change in a matter of hours or days. What might lead to improvements in clock reliability is what’s known as “single cell” analysis, wherein cells are tested one by one for their clocks. This will add even more expense to the clocks, but I would guess it will be a standard feature within the next 5-10 years. Similarly, if you take the exact same blood sample from one person and run the clock algorithm on it multiple times, you should get the same result- something known as technical replication. A potential source of noise for technical replicates is how long the sample has been sitting around or exposed to light or air, which could cause sample degradation and vary a lot, especially with mail-in blood spot tests. There are many potential fixes to this including improvements in sample collection that protect the blood or saliva from degradation.

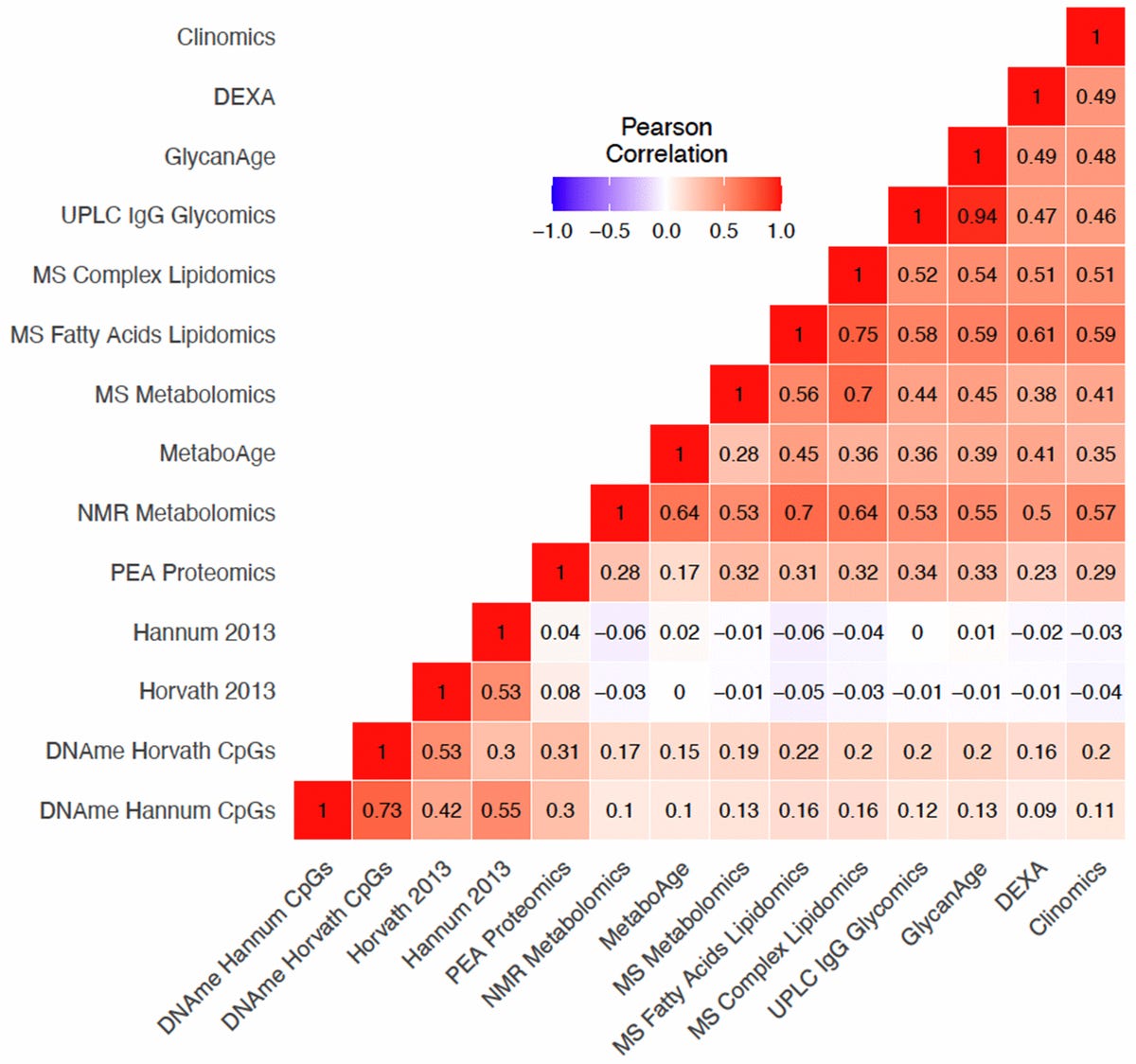

How well do the dozen or so clock tests agree with each other and which one is “right”? They agree with each other pretty well but not perfectly and some are further apart in agreement than others. Below is a correlation matrix of how well they agree with each other from a recent publication. The higher the number and the more red the box, the more in agreement two clock tests are.

Which one is “right” is a little more complicated of a question. Biological aging is not just one thing. It differs by person and by organ. Age is a risk factor for both heart disease and for Parkinson’s disease but not all people with Parkinson’s have heart disease and most people with heart disease do not have Parkinson’s disease. So aging is affecting people and organs differently. Each of the aging clock tests can very accurately tell how old a person is chronologically but what we really want to know is how long they will live and will they avoid chronic diseases. To accurately answer these questions will require more research that follows people taking the tests over time. However, this is what we know so far.

How predictive are aging clocks for your health and future healthspan? As we have published, our test made specifically for the brain (NeuroAge) can predict Alzheimer’s disease risk very well and demonstrates that if you are five years older biologically than your chronological age, your risk is pretty high (36% at age 80). However, if you are aging better than 65% of your peers and have a NeuroAge that is five years younger than your chronological age, your risk of Alzheimer’s is dramatically reduced (6% at age 80). These NeuroAge clocks also predict how fast a person without neurological diseases’ memory is declining. This is a pretty huge incentive to try and get a passing exam score for brain aging. It could be the difference between living happily and independently and requiring the assistance of nurses or an assisted living home. It is worth noting that the NeuroAge clocks are more precise because they don’t have the issue of changing cell numbers that the blood clocks have. However, they currently have the caveat of requiring a brain sample, which is not super practical. We are working on a blood/saliva version of the NeuroAge clock, which will have a beta version later this year.

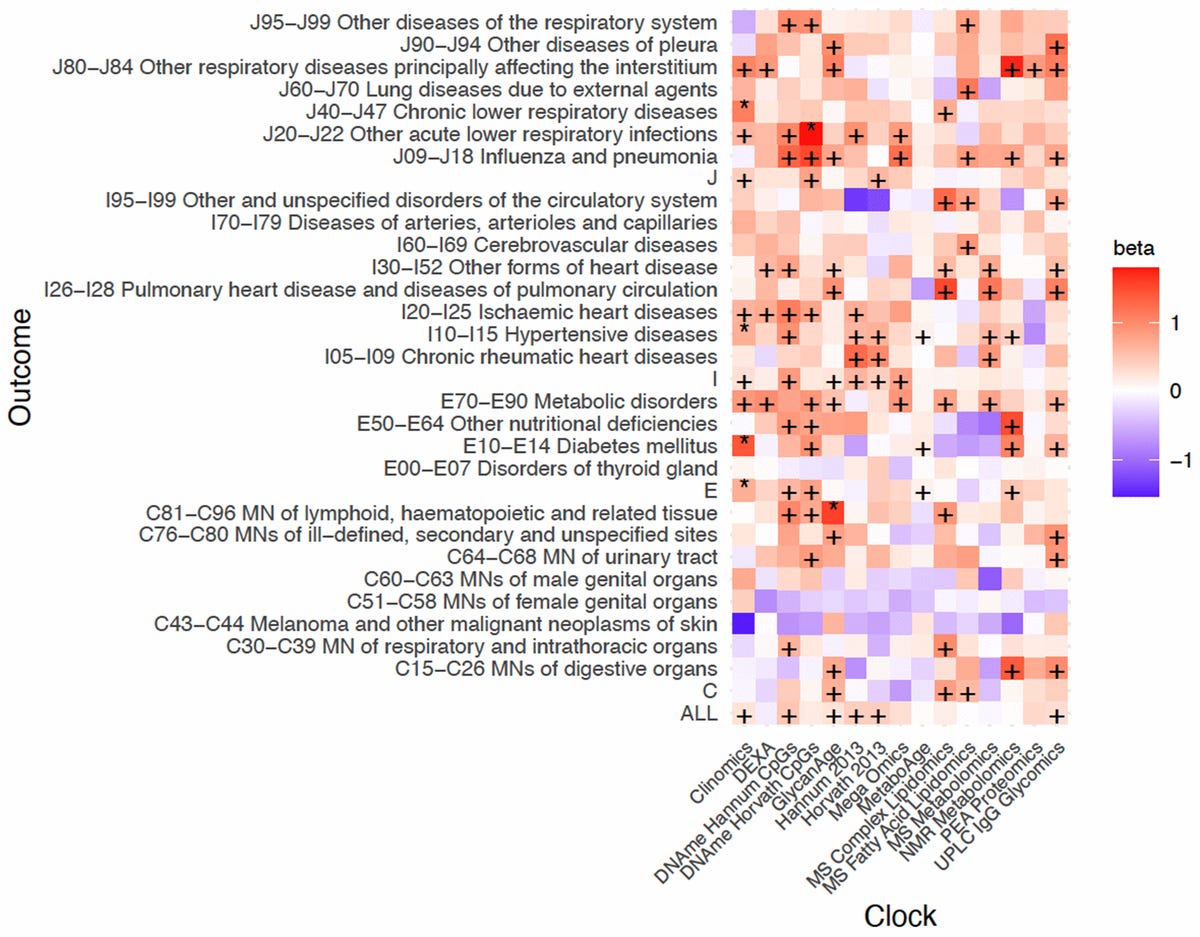

The same paper that looked at how well the various clocks agree with each other also looked at how well they predict various diseases and health outcomes. The below figure shows that these clocks can predict risk of a variety of diseases from respiratory infections to heart disease, diabetes, and cancers (+ symbols indicate statistical significance).

However, some clocks are predicting some disease outcomes better than others. And some disease outcomes are not being predicted well by almost any of the clocks- melanoma for instance. You can think of why a blood clock might not predict a skin disease very well. Perhaps someone is very healthy in terms of their lifestyle about almost everything but lives in a very sunny place, like Arizona, and doesn’t take precautions to prevent sun exposure. This person may be at risk for faster skin aging and melanoma but not other age-related health outcomes. In this case, a skin aging clock might be what’s needed to accurately predict melanoma risk. Or blood clocks could be trained specifically to estimate skin aging risk, which would be easier since it wouldn’t require a skin biopsy.

Overall I think aging clocks will be a mainstay of future preventative medicine and will compliment Fitbits, Apple Watches, and 23andMe tests in the new age of personalized “well care”. There are some things to be worked out however, including creating longitudinal datasets of clock measurements, exploring interventions, and demonstrating causal relationships to health outcomes in people. An exciting prospect that is being discussed in the scientific community is tacking on aging clocks to existing clinical trials to see if drugs for other purposes can turn back the clocks. We also need to increase the accuracy and precision of the clocks in people, perhaps by using single cell and tissue specific technology. At the same time, we need to work to bring down costs to make the clocks accessible to everyone. If you have the funds, try a few of the clocks today and let me know how well the results match with each other. Happy hacking folks!